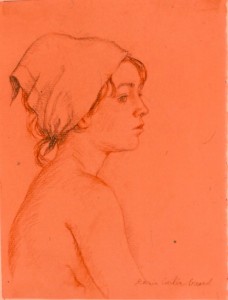

Marie Cecilia Guard’s nude portraits were remarkable. Wryly, in later years, my mother was to recall hearing my father remark approvingly at the Graphic Arts Club: “She paints more like a man.” All her life, she was to see herself as an artist rather than a woman artist. What was important to her was that she “just wanted to paint as well as the best.” Now, at the same time that she was trying to make a place for herself in illustration work, she began a daring crusade to gain recognition through the O.S.A. and R.C.A. shows. Her mural work had encouraged her to work boldly and to fill a large canvas. She recognized that the large walls of the impressive new Toronto Art Gallery [Now the AGO] demanded big pictures which drew the eye. Although landscapes dominated the exhibitions in the thirties, figures were still her subject of choice.

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”

The second picture shown that autumn was Idyl, the first of a series of stunning, life-sized or larger nudes. Idyl, later known as Nude With Chrysanthemums, is a supple, graceful back view of a drooping Margaret, ornamented with white chrysanthemums. This, and the nudes which followed, were pictures which reflected a defiant elation in the face of hardship.