My parents, lifelong artists Ken Phillips and Marie Cecilia Guard, kept Christmas in a Dickensian style which gave me much joy as a child. They believed wholeheartedly in theatre and performance as an essential part of their celebration. In fact, one of the first elements they had introduced to their two storey studio in Mississauga was a small stage for the plays they believed would surely take place there.

Because my father’s day job was in the Art Advertising department at Simpson’s in Toronto, he knew the decorators who created wondrous, elaborate decorations for the store. In those days such things were not available to buy. Because of his friendship with the decorators and his enthusiasm for their showy treasures, he often was given spares or allowed to rummage in the discard bins. This meant that often, when he arrived home from work on a December night, he pulled out of his magical shopping bags magnificent glass globes and tiny twinkling lights and sparkling swags, and gigantic scarlet velvet bows with which to garland our slender home-cut tree and the stout bamboo posts which delineated the stage. Over it all presided the brass fretwork oriental lantern from which light through the midnight blue stained glass panels pooled on the stage floor. For this special time only, the large paintings which loomed on their tall easels, stood in the studio background, taking second place to the elaborate decorations.

Yes, there was music: folk songs and carols from round the world, which brought us close to other peoples, but also the assorted cymbals, chimes, gongs and flutes which were part of the hoard he had gathered about him, sure they would be needed sooner or later.

And yes, there was entertainment. As a boy my father had been charmed by magic, and for the holiday he performed from his secret book of spells for my sister and me. And, as we sat before the dancing flames of the fire, he read “Christmas at Dingley Dell” to my mother, sister and me with huge enthusiasm, taking on all the voices to bring it to life.

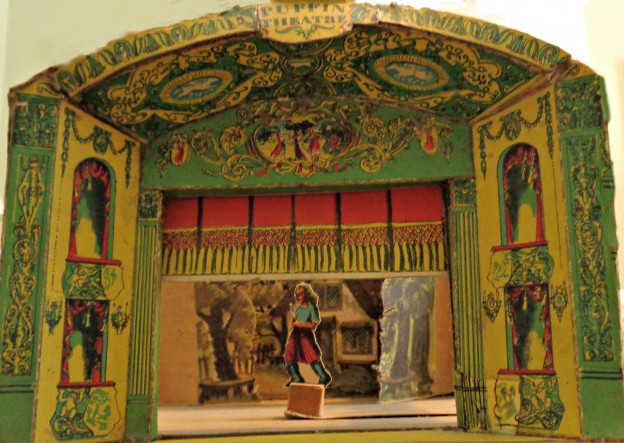

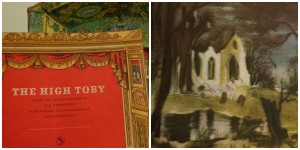

As my sister and I grew older, he searched tirelessly for amusements for us. One which gave him particular pleasure was the Puffin Theatre, published by the British children’s division of Penguin Books. This became our version of the pantomimes which were a traditional part of British holidays. He created the handsome green and yellow theatre from a series of booklets. From the main book he cut out the parts of a theatre and formed the model by gluing the parts to stout cardboard and joining them together with his favourite brown paper tape. Separate books, such as Treasure Island, included the trappings of an entire play, also ready to be cut out and reinforced. Each play came with a number of beautifully illustrated sets, the script, and even characters in costumes. These characters were slipped into tiny wooden blocks, which was glued to a piece of cardboard. By sliding the cardboard back and forth across the stage floor, we could put on our performance for our parents.

So far as I know, no play was ever produced in the small studio theatre, but at Christmastime, thanks to the tiny stage my father made, the drama he craved prevailed.

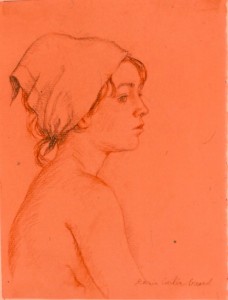

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”

She tested the climate with Margot, a life-sized portrait of her sister, in a softly ruffled dress baring her shoulder, and with her eyes provocatively downcast, which was exhibited in the spring 1934 O.S.A. show. The following autumn, the R.C.A. show included two life-sized works by Marie. Once my mother had been a frail little girl who dreamed and poured over her books of tales and legends. Now, in 1934, she painted her blonde classmate, Isabelle Dawson (later to become a successful New York illustrator), in a similarly dreamy pose looking at the book Tales of Long Ago and waiting for her lover to come and call. [illust – Once Upon a Time] Harking back to the magical 1929 O.C.A. masquerade ball on the theme “King Arthur’s Court”, where both my parents had been praised by the press for the originality of their costumes, Marie made up a background tapestry effect for this portrait. Subsequent to the R.C.A. show, this painting was exhibited across Canada. Although she was just twenty-six, author and critic Kenneth Wells, reviewing Once Upon a Time, remarked: “This lady is making rapid strides towards the front rank of figure painting.”